I started to paint with a simple paint brush and watercolors but over the years I have explored many techniques such as oils, acrylics and printmaking including etching, aquatint, linoleum block printing and wood block. With that knowledge, I have learned to let the work guide me, to choose materials and techniques according to the essence of the subject.

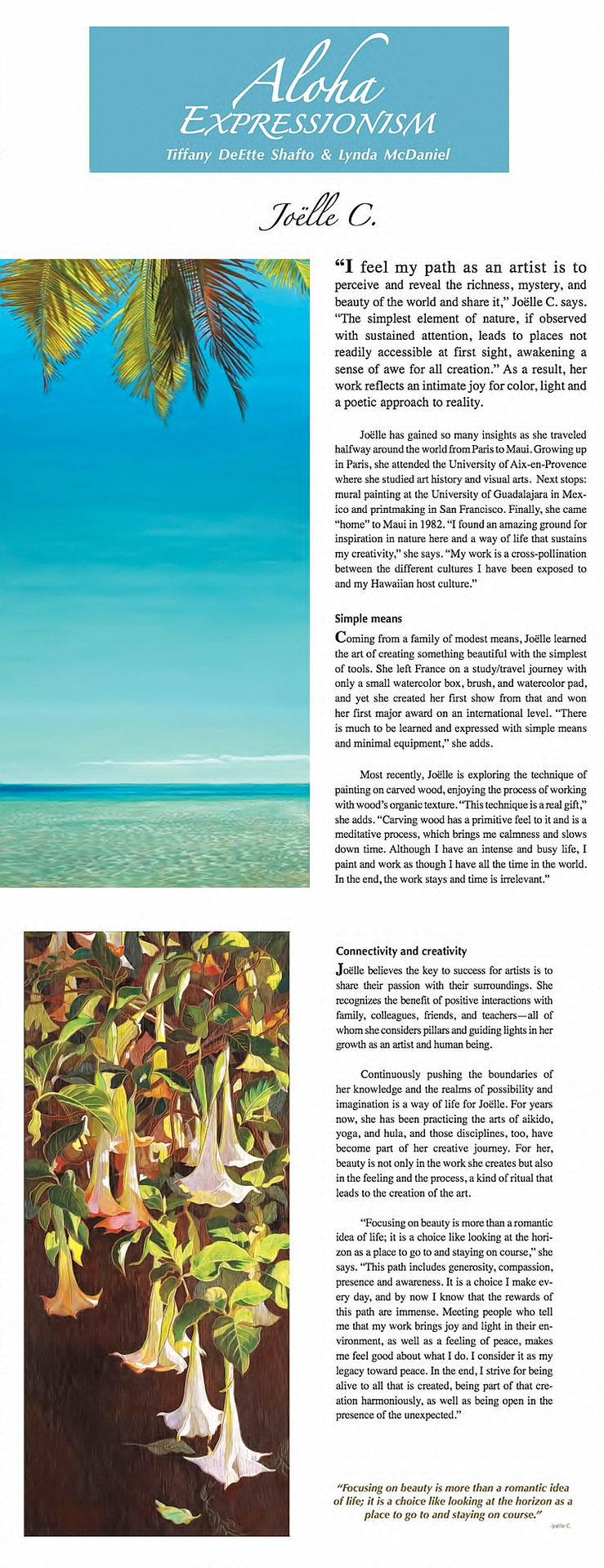

Most recently, I have been exploring the technique of painting on carved wood, enjoying the process of working with the wood’s organic texture.

I mostly work on Mahogany wood chosen for its textural qualities as well as the adequate hardness for carving. The paint is applied through different methods from a transparent glaze to a more opaque covering. I feel that to create my paintings on carved wood requires the knowledge of all the techniques I have learned over the years, therefore giving my art a unique depth and multiple dimensions.

“The technique of carving wood has a primitive feel to it and is a meditative process, which brings me calmness and slows down time. Although I have an intense and busy life, I paint and work as though I have all the time in the world. In the end, the work stays and time is irrelevant.”

Aloha Expressionism

“Keep looking,” she says.

Then I see it: the way the painting moves from an abstract background . . . to outer leaves that are more defined, but still stylized and expressive . . . to the precise and realistic detail at the flower’s core. “Lightness and Passion,” acrylic on paper, is a metaphor for the journey Joëlle Chicheportiche Perz has traveled over the years. Most artists begin with figurative work and evolve (if at all) toward abstraction. Joëlle went the other way.

When she welcomed me into her small, sunny studio, I had surveyed the varied works on those walls, monoprints, lithographs, watercolors on paper, acrylics on canvas, plaster on wood, and asked, “Which are yours?”

“All of them,” she had replied. “Each one represents a different period in my artistic journey. I consider myself an explorer of the visual phenomena.”

She grew up in Paris, surrounded by intellectualism and art. At the age of five, only slightly precociously, she realized that art was her passion; after high school, she studied fine art and art history at the University of Aix-en-Provence. “I wanted to be a professor of art at the university level,” she says. “I thought that was the one way to make a living at art.”

A visit to Montreal during her university years changed the course of Joëlle’s life. “I saw my first mural paintings there and fell in love with the idea of making art as a part of the urban landscape, art touching people’s lives on a grand scale.” For a year she worked as a waitress to pay her way to Mexico, arriving in the New World with only a small pad of watercolor paper and a pint-sized box of paints. “My first show was done with that,” she says. “I was very conscious of simplicity.”

“Keep looking,” she says.

Then I see it: the way the painting moves from an abstract background . . . to outer leaves that are more defined, but still stylized and expressive . . . to the precise and realistic detail at the flower’s core. “Lightness and Passion,” acrylic on paper, is a metaphor for the journey Joëlle Chicheportiche Perz has traveled over the years. Most artists begin with figurative work and evolve (if at all) toward abstraction. Joëlle went the other way.

When she welcomed me into her small, sunny studio, I had surveyed the varied works on those walls, monoprints, lithographs, watercolors on paper, acrylics on canvas, plaster on wood, and asked, “Which are yours?”

“All of them,” she had replied. “Each one represents a different period in my artistic journey. I consider myself an explorer of the visual phenomena.”

She grew up in Paris, surrounded by intellectualism and art. At the age of five, only slightly precociously, she realized that art was her passion; after high school, she studied fine art and art history at the University of Aix-en-Provence. “I wanted to be a professor of art at the university level,” she says. “I thought that was the one way to make a living at art.”

A visit to Montreal during her university years changed the course of Joëlle’s life. “I saw my first mural paintings there and fell in love with the idea of making art as a part of the urban landscape, art touching people’s lives on a grand scale.” For a year she worked as a waitress to pay her way to Mexico, arriving in the New World with only a small pad of watercolor paper and a pint-sized box of paints. “My first show was done with that,” she says. “I was very conscious of simplicity.”

Mexico was artistically enriching, affording Joëlle enormous opportunities for expressive growth. Still, she felt keenly the loss of a social support system, the kind of safety net France provides its citizens. For a time, Joëlle literally was a starving artist. She persevered, and by 1975 had not only received her first mural commission, she’d won first prize for a painting in honor of the International Year of the Woman.

That’s when she decided to leave. “I was twenty-four and it was becoming too easy. I could see myself becoming better known, but I wanted to keep learning. I longed for more challenges.”

In 1977 Joëlle moved to San Francisco, and studied printmaking, a craft she has continued to develop throughout her artistic career. She also found herself plunging into the melting pot, trying to adapt to a new country, a new language, and survival in the big city. “Each time I have moved to a new country, I have had to let go of patterns and prejudices. The robes of cultural conditioning fall away, and you become naked. I have had to let go of a lot of things to follow my heart.”

Mexico was artistically enriching, affording Joëlle enormous opportunities for expressive growth. Still, she felt keenly the loss of a social support system, the kind of safety net France provides its citizens. For a time, Joëlle literally was a starving artist. She persevered, and by 1975 had not only received her first mural commission, she’d won first prize for a painting in honor of the International Year of the Woman.

That’s when she decided to leave. “I was twenty-four and it was becoming too easy. I could see myself becoming better known, but I wanted to keep learning. I longed for more challenges.”

In 1977 Joëlle moved to San Francisco, and studied printmaking, a craft she has continued to develop throughout her artistic career. She also found herself plunging into the melting pot, trying to adapt to a new country, a new language, and survival in the big city. “Each time I have moved to a new country, I have had to let go of patterns and prejudices. The robes of cultural conditioning fall away, and you become naked. I have had to let go of a lot of things to follow my heart.”  Throughout her years of study, Joëlle had sold very little of her work. She’d been in no hurry to “make a statement” in the art world, preferring to pursue her quest for knowledge. “This slow growth enabled me to enjoy not only the product of creation but also the process,” she recalls.

“The galleries wanted me to do the underwater paintings that were so popular. I had no money, and still I said no. I would never have gotten to the places I need to be if I had said yes.”

To support herself, Joëlle taught. She worked on boats. And always, she studied. “I learned to let the work guide me, to choose materials and techniques according to the essence of the subject.”

Her willingness to let go, and the training that enables her to “bring all the tools to the task,” have combined in Joëlle to create an openness and readiness that seem to draw serendipity’s blessings like a magnet. Each time she risks, she advances on the path to deeper understanding.

Throughout her years of study, Joëlle had sold very little of her work. She’d been in no hurry to “make a statement” in the art world, preferring to pursue her quest for knowledge. “This slow growth enabled me to enjoy not only the product of creation but also the process,” she recalls.

“The galleries wanted me to do the underwater paintings that were so popular. I had no money, and still I said no. I would never have gotten to the places I need to be if I had said yes.”

To support herself, Joëlle taught. She worked on boats. And always, she studied. “I learned to let the work guide me, to choose materials and techniques according to the essence of the subject.”

Her willingness to let go, and the training that enables her to “bring all the tools to the task,” have combined in Joëlle to create an openness and readiness that seem to draw serendipity’s blessings like a magnet. Each time she risks, she advances on the path to deeper understanding.

“In the past I had huge revelations. Now they are more subtle. Some you might not notice at first, and yet to me they can be stunning or simply delightful. Like the way a color that appeared dull suddenly brightens and becomes luminous when associated with another color; or the change of mood an object evokes, depending on the light that shines on it. I also found that if you focus on beauty, beauty will surround you. That is the greatest reward of my work.”

It’s a vision and reward she shares with her husband, Oliver Perz, a mechanical engineer who has become her manager and her partner in creating the environment they call home. Seven years ago the couple purchased two acres in Kula along the edge of a ravine. They cleared out scrub and planted beds of flowers, fruit trees, and vegetable gardens. A terraced path leads down to the canyon floor, and the gazebo that is Joëlle’s sometime studio. A pohaku wall, the remains of an ancient route to the crater summit, lies along the dramatic cliffs at the property’s far boundary. A rocky depression an unexpected feature revealed during the clearing will form a natural basin for the lily pond Joëlle and Oliver have planned; the transformation is ongoing.

As is Joëlle’s.

“I draw a lot of inspiration from my garden,” she says, “but I don’t necessarily paint it. Some things I like to leave alone, letting the stones keep their secret and giving me a chance to discover them with new eyes every day. The passing moment, the joy and playfulness of the light, the mystery of shadows, the universal quality of a single flower, this I like to capture.”

“In the past I had huge revelations. Now they are more subtle. Some you might not notice at first, and yet to me they can be stunning or simply delightful. Like the way a color that appeared dull suddenly brightens and becomes luminous when associated with another color; or the change of mood an object evokes, depending on the light that shines on it. I also found that if you focus on beauty, beauty will surround you. That is the greatest reward of my work.”

It’s a vision and reward she shares with her husband, Oliver Perz, a mechanical engineer who has become her manager and her partner in creating the environment they call home. Seven years ago the couple purchased two acres in Kula along the edge of a ravine. They cleared out scrub and planted beds of flowers, fruit trees, and vegetable gardens. A terraced path leads down to the canyon floor, and the gazebo that is Joëlle’s sometime studio. A pohaku wall, the remains of an ancient route to the crater summit, lies along the dramatic cliffs at the property’s far boundary. A rocky depression an unexpected feature revealed during the clearing will form a natural basin for the lily pond Joëlle and Oliver have planned; the transformation is ongoing.

As is Joëlle’s.

“I draw a lot of inspiration from my garden,” she says, “but I don’t necessarily paint it. Some things I like to leave alone, letting the stones keep their secret and giving me a chance to discover them with new eyes every day. The passing moment, the joy and playfulness of the light, the mystery of shadows, the universal quality of a single flower, this I like to capture.”

Light. Enlightenment. I should have known. I remember that Joëlle is an avid student of aikido, a martial art that teaches you to center your being and focus your energy. From this source, too, Joëlle has drawn the confidence to trust.

“What I am looking for is simplicity,” she says, “the balance and peace of mind that enable me to do my art, express my passion for life, and create a little more happiness in this world. I love when people tell me they find a healing in my work.”

Light. Enlightenment. I should have known. I remember that Joëlle is an avid student of aikido, a martial art that teaches you to center your being and focus your energy. From this source, too, Joëlle has drawn the confidence to trust.

“What I am looking for is simplicity,” she says, “the balance and peace of mind that enable me to do my art, express my passion for life, and create a little more happiness in this world. I love when people tell me they find a healing in my work.”  “When it comes to style, labels and categorizations simply slide off her shoulders, and a unique blend of tradition and creativity comes to mind. She is free to produce the most expressive, refined statement with the delicate touch of a master, giving the viewer a fundamental feeling of peace.”

— Maui News

“When it comes to style, labels and categorizations simply slide off her shoulders, and a unique blend of tradition and creativity comes to mind. She is free to produce the most expressive, refined statement with the delicate touch of a master, giving the viewer a fundamental feeling of peace.”

— Maui News